Protecting Farmers from Weather-Based Risk

ATAI evidence synthesis discussion

Photo credit: IRRI

Weather index insurance protects farmers against losses from extreme weather and facilitates investment in their farms, but randomized evaluations have shown low demand for these products at market prices suggesting the need for alternative approaches.

This page summarizes ATAI’s policy bulletin on the impact of weather index insurance, “Make It Rain” and ATAI’s policy briefcase on the impact of Swarna-sub1, “Resilient Rice.” It was written by ATAI staff, originally published on the J-PAL website at this link.

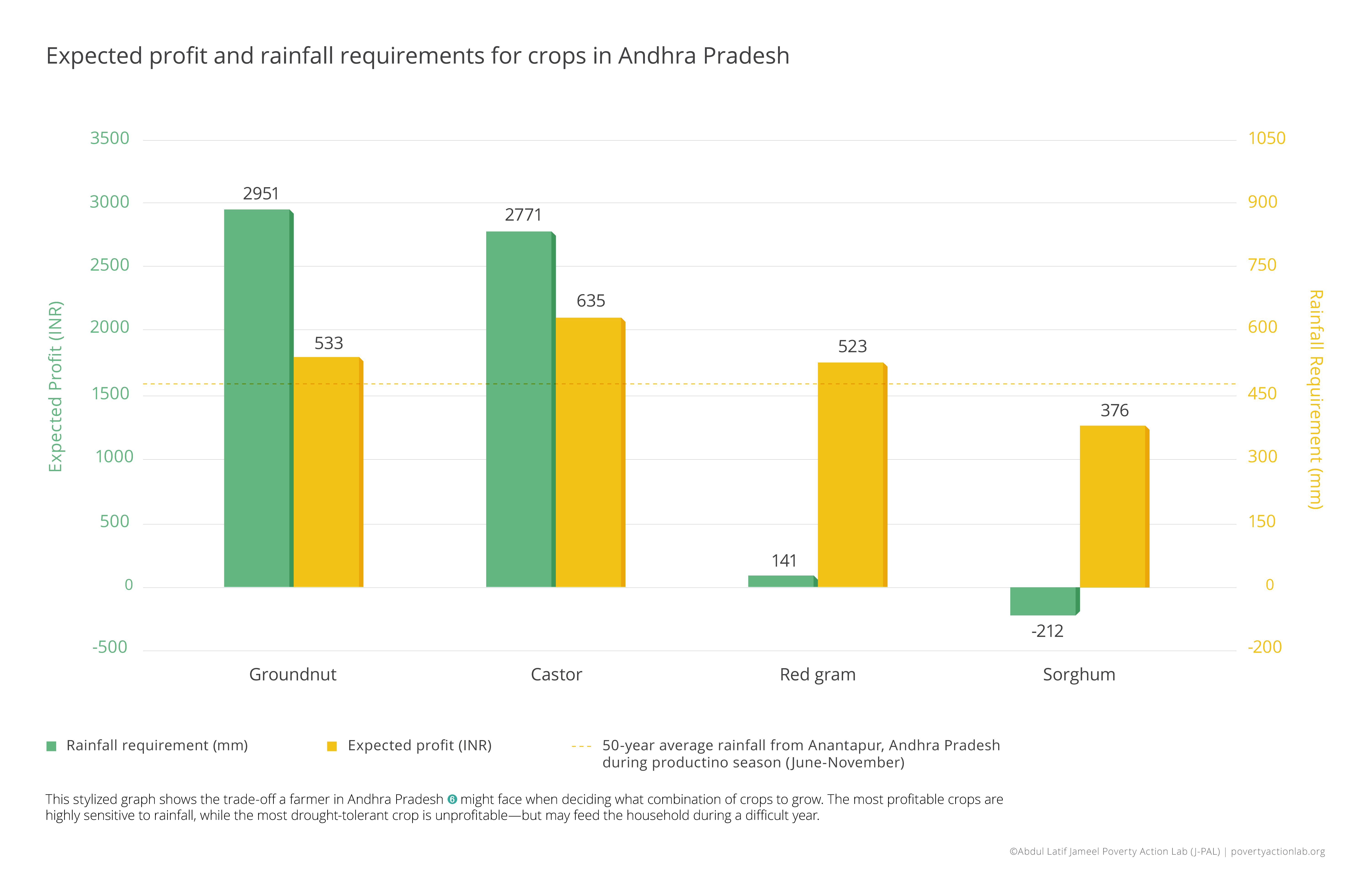

Floods, droughts, heat waves, cold spells, and other natural disasters are large sources of risk for farmers. A drought, heat wave, or other disaster can lead to a poor harvest, leaving uninsured farming households with little income for the season. In order to cope with unpredictable weather, farmers often plant low-risk, low-return crops instead of investing in more profitable crops that are more sensitive to weather. Furthermore, farmers wary of bad weather may hesitate to make other investments in their farms, such as increasing fertilizer use. As a result, the threat of extreme weather can trap farmers in a cycle of low productivity.

Insuring against weather-based losses

The evaluations took place in Ethiopia, Ghana, India (Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat, 2006; Andhra Pradesh, 2009; Gujarat, 2009; and Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Uttar Pradesh, 2010), and Malawi.

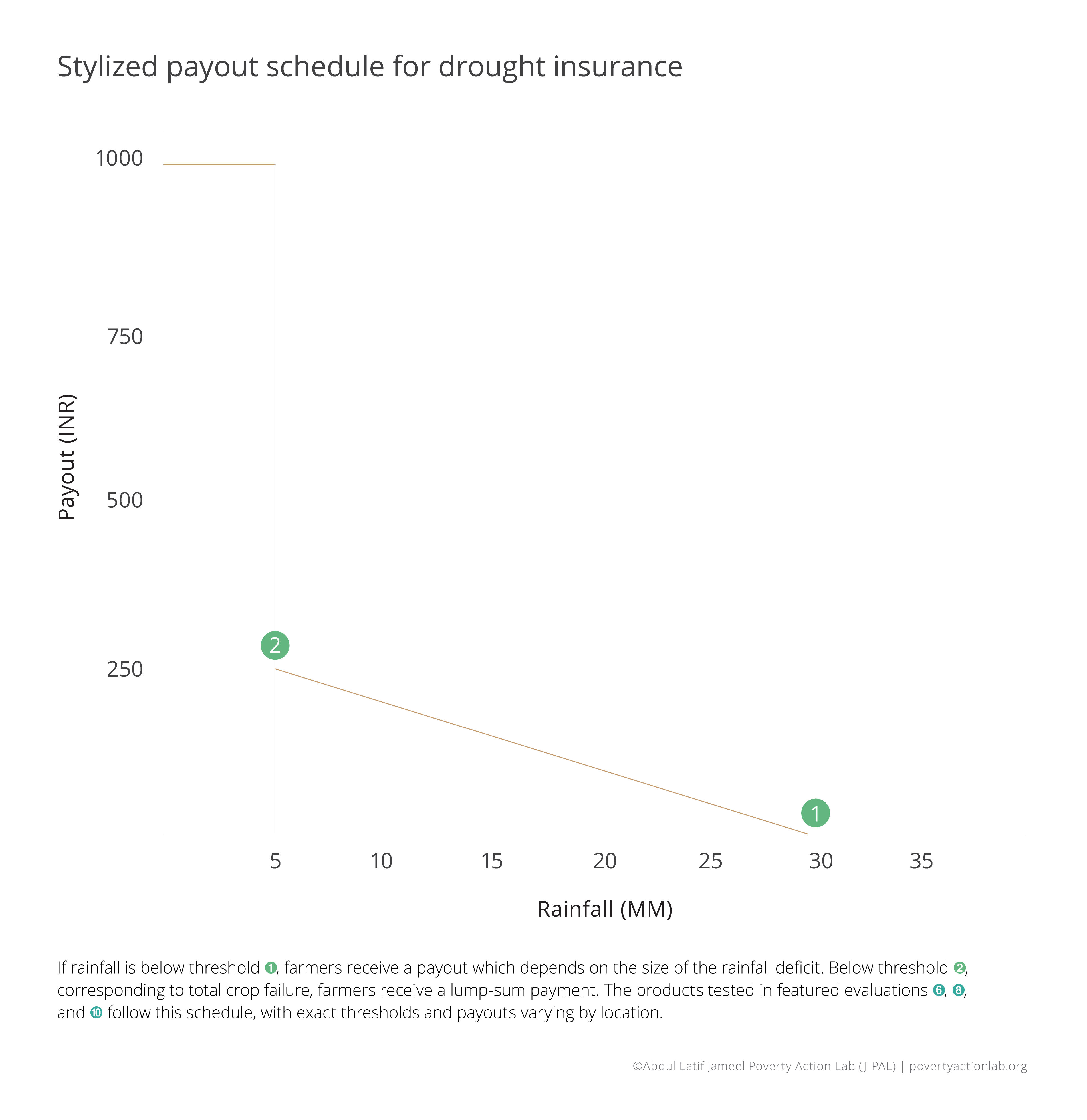

Weather index insurance, which makes payouts based on an easily observable variable such as rainfall, is an innovative financial product designed to make insurance accessible to poor smallholder farmers. Weather index insurance was first offered in the early 2000s, and it is now marketed to individual farmers in over fifteen countries. The ten randomized evaluations summarized in “Make it Rain” tested take-up of weather index insurance products and, in three cases, effects on agricultural production decisions.

Key Results

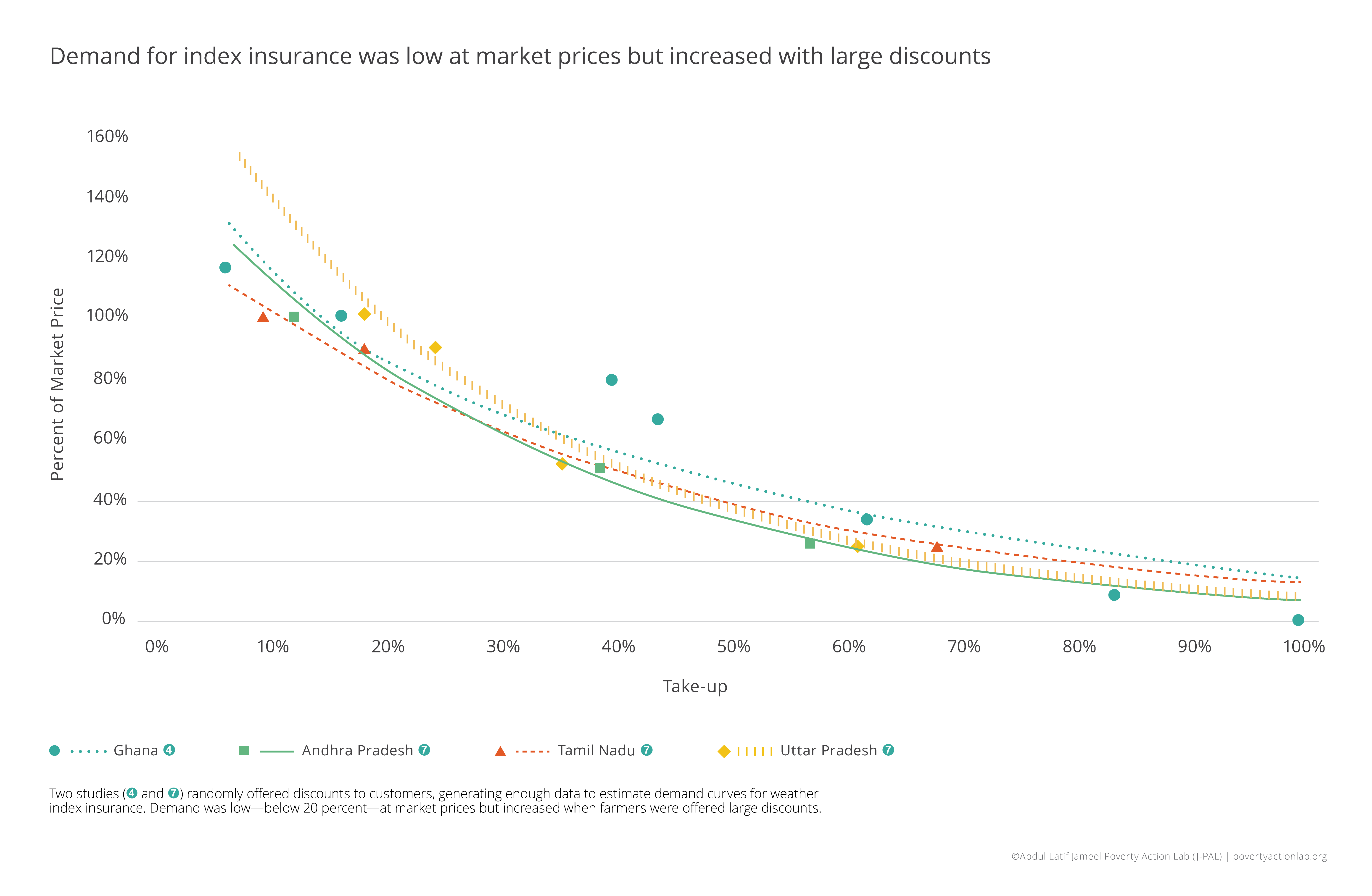

Without substantial subsidies, take-up of insurance was low.

Large discounts increased take-up substantially and interventions designed to increase financial literacy or reduce basis risk also had positive effects. However, at market prices, take-up was in the range of 6–18 percent, which cannot sustain unsubsidized markets.

Insured farmers were more likely to plant riskier but higher-yielding crops.

In the three studies that measured changes in farmer behavior, farmers who felt protected against weather risks shifted production toward crops that were more sensitive to weather but more profitable on average.

Policy Lessons

Weather risk remains an important barrier to agricultural development. Although low demand has prevented markets for commercial weather index insurance from scaling, in cases where farmers were given subsidized insurance, the protection led them to make investments to increase farm productivity. These facts point to the need to study a range of alternative approaches to address weather risk.

Farmers’ lack of interest in purchasing insurance has limited the growth of commercial markets.

Many insurance providers rely on generous government subsidies, technical assistance from aid agencies, or bundling insurance with more popular products.

Insured farmers made different production decisions, underscoring how weather risk limits farmers.

They shifted production toward crops that were more sensitive to weather but more profitable on average. Whether through index insurance or another approach, providing protection against weather risk may be a crucial step in getting farmers to plant cash crops, use more fertilizer, and make other investments to increase production.

Weather index insurance has fallen short of an elusive goal: becoming an insurance product that can be profitably sold to poor farmers.

This points to the need to research alternatives that help smallholder farmers manage weather risk, including:

- Improving index design. Using indices based on yields, rather than weather, may reduce basis risk, especially with remote sensing technologies that can accurately measure yields for small areas. These improvements, which increase data quality and better tailor payouts to actual risks, may allow insurers to offer products that more effectively protect farmers from the risks they face.

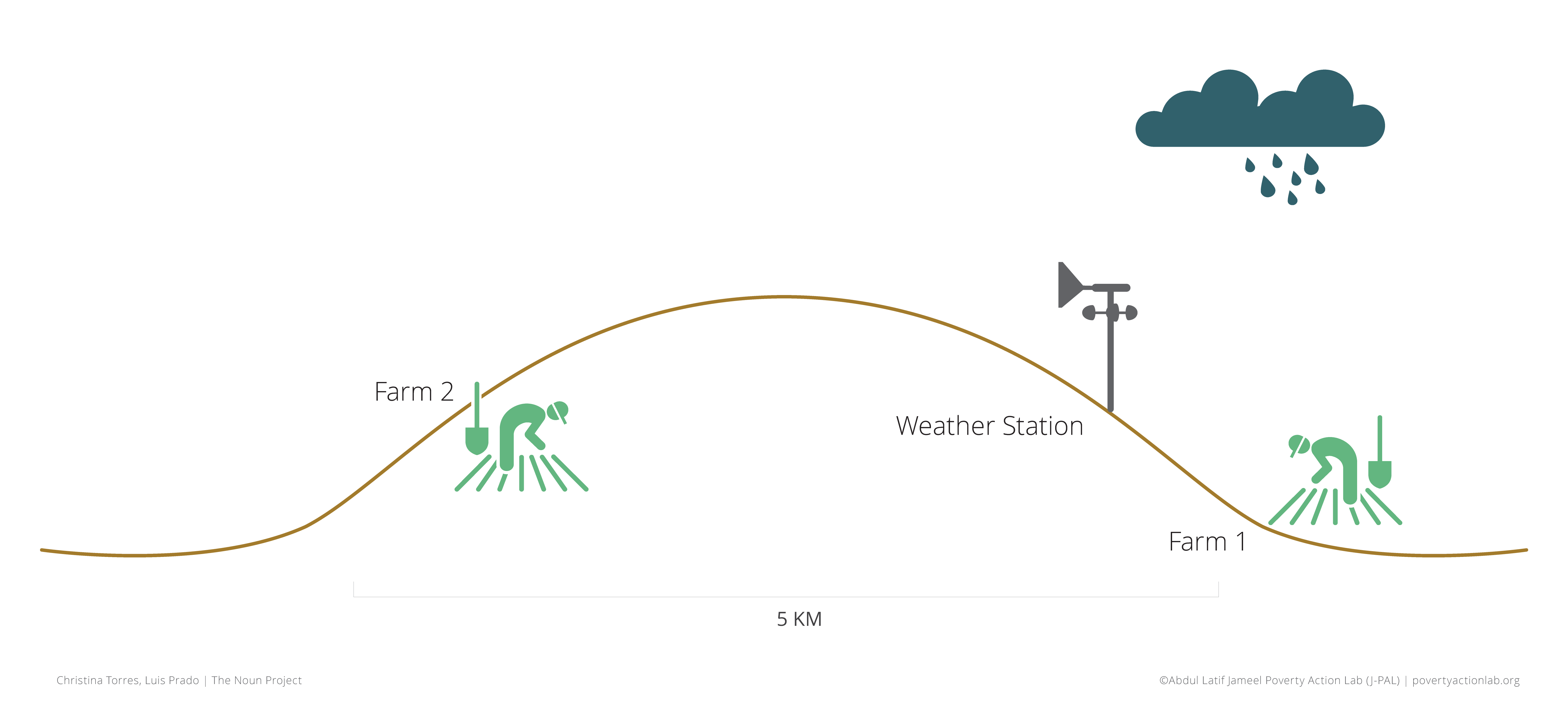

Basis risk is the risk that the index will not accurately predict a farmer’s loss. Farm 2 experiences a poor harvest, but rainfall at the weather station is adequate, so there is no payout.

- Using subsidized insurance to deliver cash to farmers. The studies that gave away free insurance (Ghana and Andhra Pradesh, India) compensated comparison group farmers with cash grants. While insurance led farmers to shift production toward higher-value crops, receiving cash did not. For policymakers seeking to influence farmers’ production decisions, large insurance subsidies may be more effective than cash transfers. Over time, experience with subsidized insurance may increase farmers’ willingness to pay for these products.

- Selling insurance to institutions that are also affected by weather risk. Weather shocks are a source of risk for agricultural lenders as well as governments providing disaster relief or social safety net programs. Unlike individual farmers, banks and government agencies cover broad geographic areas, which reduces basis risk. Although this approach has not yet been rigorously tested, insurance providers have begun to offer these products, which have the potential to both protect institutions and increase credit supply.

- Promoting irrigation and stress-tolerant crops. Most smallholders rely on rain-fed agriculture, so improving irrigation systems is a natural first step in helping them cope with variation in rainfall. In addition, agricultural research centers have developed crop varieties that tolerate conditions such as drought, flood, and salinity while maintaining good yields under normal conditions. Similar to the impact of insurance on farmer decision-making, risk-mitigating technologies such as submergence-tolerant rice allow households to make riskier production decisions, including input purchasing. In the event of a weather shock, farmers using risk-mitigating technologies and laborers on these plots are protected from a large loss in absolute yields, whereas insured farmers that made riskier planting decisions face crop loss. Results from India are promising: farmers planting a flood-tolerant rice variety planted more rice, used more fertilizer, and used better planting techniques.

Structurally reducing risk through improved seeds

This evaluation took place in Odisha, India in 2011 and 2012.

While self-sustaining markets for weather index insurance have not emerged, finding ways to address weather risk remains a priority for agricultural development. One promising alternative is to explore other risk-mitigating technologies, such as improved seeds that better tolerate weather events. Crop varieties that reduce losses during flooding or droughts and maintain yields during normal years may be more appealing to farmers than insurance while still allowing households to take on more risk in decisions such as input purchasing. These are breeder-selected varieties of common seeds that maintain high yields if a drought or flood occurs.

Swarna-Sub1 is one example of a resilient breeder-selected variety and was developed by researchers from the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). To create Swarna-Sub1, CGIAR inserted a flood-resistant gene called Sub1 into the popular Swarna rice variety. Swarna-Sub1 is nearly identical to Swarna, the most popular rice variety in India, but can tolerate submergence for up to two to three weeks without the flood conditions affecting yields.

Key Results and Policy Lessons

Stress-tolerant crops can reduce risks to farmers and make them more resilient in the face of climate shocks.

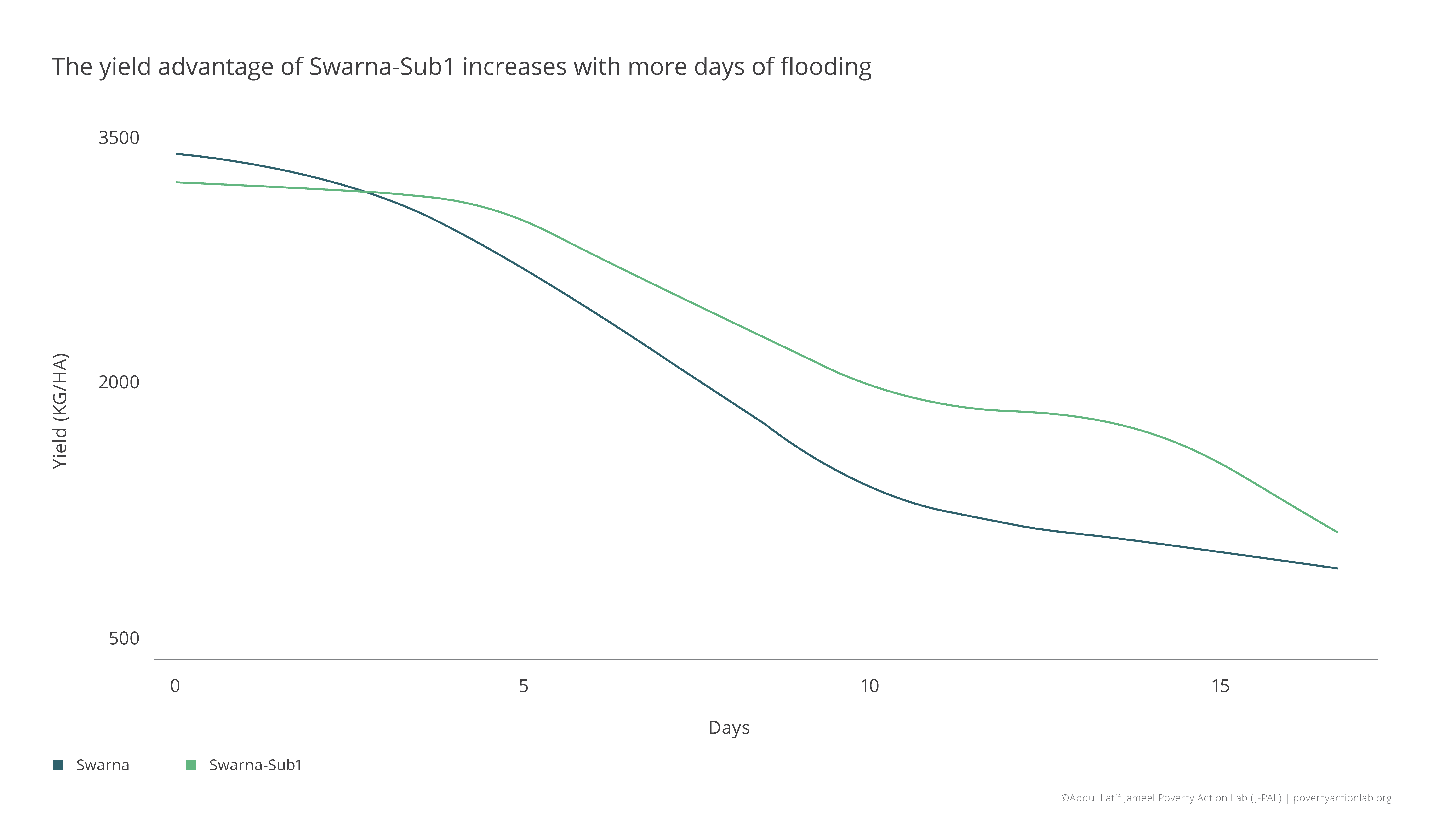

Access to Swarna-Sub1 seeds reduced losses in yields by an average of 10 percent per hectare with even greater losses among farms that experienced more days of flooding. In areas without flooding, there was no significant difference in yield between the two varieties, indicating that there was no disadvantage to planting Swarna-Sub1 in non-flood years.

In addition, because Swarna-Sub1 is highly similar to Swarna, with which many farmers in India are familiar, switching to Swarna-Sub1 does not require significant changes in behavior or an extensive information campaign—a sharp contrast with more complex innovations designed to address risk, such as weather index insurance.

Access to Swarna-Sub1 led farmers to invest more in their farms.

Swarna-Sub1 protected against the risk of unpredictable flooding, so farmers had less need to self-insure by making conservative planting and investment decisions. This resulted in a number of changes to farmer behavior including cultivating additional land, increasing investment in inputs, adopting improved planting techniques, and changing savings and credit decisions. These investments led to higher rice yields even when no floods occurred. This suggests that risk-reducing seeds have additional benefits beyond those that accrue during weather shocks because they can lead farmers to make more productive investments in their farms.

Stress-tolerant crops may help address issues of inequity.

Scaling up Swarna-Sub1 to flood-prone areas would benefit marginalized farmers the most. In India, members of Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes tend to cultivate low-lying, flood-prone land and would therefore likely experience the greatest yield improvements from the adoption of flood-tolerant rice. To the extent that marginalized groups around the world tend to farm less desirable pieces of land, the development and adoption of weather-tolerant crops could help mitigate the effects of entrenched inequalities.