Overview

Researchers

Andrew Dillon

Associate Research Professor, Northwestern University

Nicoló Tomaselli

Research Director, University of Zurich

- Country

- Mali

- Timeline

- 07/01/2017 - 12/30/2018

- Constraints

- Credit

- Technology Category

- Fertilizer, Inputs

Photo Credit: © Curt Carnemark / World Bank

In many parts of sub-Saharan Africa, few farmers use inputs like fertilizer to increase farm productivity, and when they do, many use too few inputs to maximize productivity. Among other factors, like high transaction costs, access to credit and the timing of input availability affects farmers’ demand for agricultural inputs. In Mali, researchers conducted a randomized evaluation to test how the design and timing of a physical market for inputs (village input fairs) with varying levels of credit access affected farmers’ investment decisions. Farmers with access to credit from VIFs organized after harvest increased their demand for inputs while farmers offered VIFs at planting without access to credit did not. This suggests that both the timing of the VIF and liquidity were critical components of spurring input demand.

Policy issue

In many parts of sub-Saharan Africa, few farmers use inputs, like fertilizer, to increase farm productivity, and when they do, many farmers use too few inputs to maximize productivity. Inputs can be costly, and farmers often have to travel long distances to reach markets to purchase them. Among other factors, access to credit and the timing of input availability also affect farmers’ demand for agricultural inputs. In addition to these constraints that farmers face, agro dealers, whose business is to sell agricultural inputs to farmers, also face challenges. Specifically, they face high transportation costs to reach remote areas and lack information about farmers’ demand for their products.

One way to support both farmers and agro-dealers is through Village Input Fairs (VIF). VIFs are one-day markets that allow farmers to buy agricultural inputs from agro-dealers at a central location in a village rather than having farmers travel to the closest city. Typically, markets are organized during the planting season when farmers need to use inputs like fertilizer to plant their crops but are, in general, more cash constrained given the duration of time since selling their last harvest. Agro-dealers also face logistical constraints in delivering large quantities of fertilizer in the relatively short planting period. Could varying the timing of the input market and providing credit help alleviate farmers’ cash constraints and affect farmers’ likelihood of using more productive inputs?

Context of the evaluation

Agriculture is Mali’s main source of economic activity, despite the fact that 65 percent of the land is desert or semidesert.1 Sixty percent of people work in agriculture and roughly half the population lives in poverty.2 Households typically depend on agriculture for their livelihoods, their work is labor-intensive, and they have limited access to agricultural inputs, like equipment, water, labor, seeds, fertilizers, or insecticides. Transaction costs are a major barrier to input purchase and use, exacerbated by the cost of transporting inputs to rural markets, which accounts for around one-third of their total price. In addition, agro-dealers, credit providers, and farmers are often unable to connect at the times when farmers need to be able to access markets to purchase inputs. For example, 70 percent of small-scale farmers participating in this evaluation reported that they did not have access to an agro-dealer in their village in the agricultural season prior to the study. Despite limited access to agro-dealers, around 85 percent of farm households reported using fertilizer prior to the start of the study, but often use sub-optimal quantities recommended by agronomists.

This study was conducted among rural households in the Sikasso, Koulikoro, Kangaba, and Bananba regions of Mali. Eligible farmers in these regions mainly produced millet, rice, and cotton among other crops, and cultivated approximately 8.3 hectares across six plots. Although Soro Yiriwaso, a microfinance institution that engages in agricultural lending, has operated in Mali for over twenty years, farmers have limited access to credit because they often lack the collateral needed to take out loans. Participating agro-dealers operated locally and primarily supplied farmers with inputs including fertilizer, improved seeds, pesticides, and equipment from their shops in nearby towns. The National Union of the Agro-Input Dealers (UNRIA) is the primary national association of agro-dealers and plays an active role in agricultural policy.

Details of the intervention

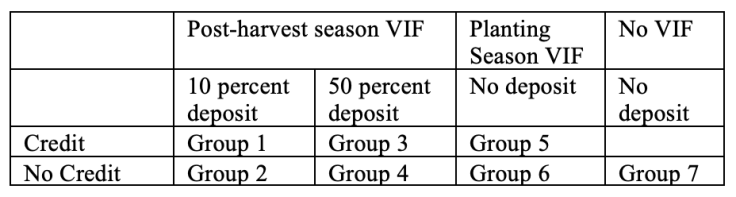

Researchers collaborated with Soro Yiriwaso, UNRIA, and Innovations for Poverty Action to conduct a randomized evaluation to test the impact of varying input market organization on farmers’ decisions to use inputs and their agricultural productivity. Researchers randomly assigned 140 villages to one of seven groups, comprising twenty villages each. The groups varied across three characteristics: the timing of agricultural input fairs, the up-front payment required for purchasing inputs, and access to credit.

UNRIA and Soro Yiriwaso organized an input fair in six out of the seven groups. The remaining group served as a comparison group and did not host an input fair. At the village input fairs (VIFs), participating farmers could place orders for agricultural inputs from agro-dealers. Researchers varied the timing of the input fairs, either after the harvest in January or at the start of the planting season in June. Agro-dealers then delivered the purchased inputs to farmers at the beginning of the planting season.

Of the six groups that hosted VIFs, farmers in three were offered credit by Soro Yiriwaso at the input fair. When the VIF was organized during the post-harvest season, farmers were required to pay an up-front deposit as a percentage of their purchase order, which acted as a commitment mechanism to secure the inputs. Farmers in one group were asked to make a 10 percent deposit on their purchase, a “soft” commitment, and farmers in another were asked to make a 50 percent deposit, a “hard” commitment. Farmers were required to pay the remaining balance at the time the agro-dealers delivered the inputs in June. If farmers were to renege on their purchase, the deposit paid at the VIF would be given to the agro-dealer.

The full breakdown of the groups was as follows:

Researchers carried out the evaluation between 2017 and 2018. Through household surveys before and after the intervention, researchers measured farmers’ decision to use inputs, particularly fertilizer, which crops they chose to plant, and labor decisions. Researchers also collected data on market transactions and input sales during the fairs.

Results and policy lessons

Farmers with access to credit from VIFs organized after harvest increased their demand for inputs while farmers offered VIFs at planting without access to credit did not, suggesting that the timing of the VIF and access to credit were both critical components of spurring input demand.

Village participation in VIFs: All villages assigned to hold VIFs during the planting season (groups 5 and 6) organized the fairs. This was not the case for villages assigned the post-harvest VIFs with deposit requirements of 50 and 10 percent, where between 45 and 80 percent of villages held the VIFs, respectively. Some village leaders assigned to the 50 percent deposit group with access to credit (group 3) refused to organize the VIFs because they considered the deposit requirement too high and risky for their communities. Despite lower participation among some villages, farmer participation in VIFs ranged between 18 to 24 percent in post-harvest VIFs and 53 percent in VIFs organized during planting.

Demand for Inputs: Participating farmers increased their demand for inputs, particularly for fertilizer. Farmers in groups 1-5 used between XOF 38,577 and 47,470 (US$66 – 81) more fertilizer throughout the agricultural season compared to XOF 167,750 (US$196.48) total for those without access to a VIF (group 7) (a 23 to 28 percent increase). Farmers offered input markets at planting without credit (group 6) did not increase their fertilizer use compared to group 7. Researchers explained that both the timing (post-harvest rather than at planting) or alleviating liquidity constraints at planting could have driven the increase in fertilizer use as groups 1 and 5 experienced similar effects of increased fertilizer demand.

Access to VIFs also encouraged farmers not previously using fertilizer to adopt it, despite high fertilizer use among farmers prior to the intervention. Farmers in groups 1, 3, 4, and 5 were between 9.6 and 13.7 percentage points more likely to begin using fertilizer than those in the comparison group (an 11 to 16 percent increase). Farmers offered access to VIFs at planting without credit were no more likely to adopt fertilizer than the comparison group. Researchers highlighted that the increase in fertilizer adoption from already high levels of use demonstrated how VIFs could contribute to supporting farmers in the most remote areas adopt productive inputs, addressing what is referred to as the “last-mile problem,”.

Agricultural productivity, crop choice, and labor: Across all groups (groups 1–6), farmers’ yields did not increase. Farmers with access to VIFs also did not consistently update their decisions on the crops they grew. However, farmers offered access to the post-harvest VIFs without credit (groups 1 and 2) and those who received the VIF during planting with credit (group 5) did increase the number of days dedicated to planting by 25, 34, and thirty days respectively. Farmers similarly increased the number of days dedicated to weeding. Farmers with access to VIFs did not hire more labor, except for farmers who gained access to the post-harvest VIFs (group 1). Researchers explain that creating an input market alone may not be enough to unlock farmers’ productivity and improve their overall welfare in a single agricultural season given limited markets for insurance, land, and water-control technologies which may also be needed to contribute to increased productivity.

Taken together, VIFs organized in the post-harvest period with credit access were the most effective model to spur farmers’ demand for inputs, particularly fertilizer.

Use of Results:

Informed by the results of this study, researchers are scaling a version of the VIF in Mali, Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana. The bundle includes the village input fair organized after the harvest, with the 10 percent commitment device, and access to credit. Researchers are conducting a randomized evaluation to test a market-based approach to scaling up this bundled VIF model on the purchase and use of inputs by small-scale farmers as well as the profitability of agro-dealers.