Building a Digital Marketplace for Agriculture in Uganda

A blog by Lauren Falcao Bergquist (University of Michigan) and Craig McIntosh (UC San Diego)

This post reports on the results of one of the largest market information experiments ever conducted, using mobile phone-based SMS and a new digital trading platform aimed at making core food markets in Uganda more efficient. Billions of dollars invested in transport infrastructure such as railroads and highways can be powerful tools in creating integrated local markets (Casaburi et al., 2012, Donaldson 2018); this study ask how much of this local integration effect can be generated with a million-dollar investment in informational infrastructure.

The core target of a market information intervention is to decrease search costs. What should the effect of this be? Noting that search costs can lead to violations in the Law of One Price, in which prices between markets differ by more than the transport costs, several studies focus on the power of improved information flows to generate greater price convergence (as in Jensen 2010 or Allen 2014). Other studies suggest that search costs are a direct source of market power for intermediaries, who can use superior information to extract rents from farmers (as in Arkolakis & Costinot 2012 or Goyal 2010), and therefore that a richer information environment may lead to greater competition among intermediaries and improved prices for the farmers from whom they buy. Our study tests both margins.

Using high-frequency market price surveys, trader surveys, and farmer surveys, we explore whether the introduction of a large-scale market platform increases market integration, reduces intermediary profits, and improves farmer welfare.

The Platform

The treatment was multifaceted, designed to shift both information and outside trading options. The overarching premise of our study was that while price information alone may not create actionable opportunities for farmers (Fafchamps & Minten 2012; Camacho and Conover, 2011), the concerted combination of up-to-date price information with new trading opportunities may be able to generate real benefits for farmers.

To test the impact of this system, we ran a multi-year experiment across 11 districts of Uganda, representing 14% of the surface area of the country. First, we worked with computer scientists at Uganda’s Makerere University and Microsoft Research who had developed a digital trading platform called Kudu that lets buyers and sellers post bids and asks to a nationwide marketplace via SMS, and matches up sellers with the best buyers. Second, we collaborated with a major private sector agricultural company called AgriNet, which trained field agents to market and promote the system on the ground and to help broker trades on the platform. Finally, we engaged in large-scale collection and experimental distribution of market-level price information, sent via an “SMS Blast system” to all traders and randomly selected farmers in treatment areas.

These interventions were randomized at the level of the 110 sub-counties throughout our study area, covering 236 “trading centers” (markets and their associated catchment areas). Trading centers were categorized as “hubs” (large-scale district markets) and “spokes” (smaller rural markets). In total, the SMS Blast System pushed out price information to 1000 large commercial buyers, 1,411 farmers, 902 traders and 171 of AgriNet’s Commission Agents (CAs). Information was sent every two weeks for three years, meaning that we contacted individuals to provide price information more than 270,000 times as a part of the study.

This was a long run study, with the platform running for three years between when the baseline and endline surveys were run.

Trade on the platform

Over the course of a three-year intervention, our system saw 23,768 asks (offers to sell) posted by over 4,000 unique users, for a total of $42 million in asks. 30,499 bids (offers to purchase) were posted by just under 3,000 unique users, for a total of $65 million. While the platform had some activity in 26 different commodities, half of the flow of bids and asks was in maize, 13% in beans, and the remainder split among small activity in other crops. The system generated 1,306 completed and verified sales, moving about 8,000 tons of grain.

Buying on the platform was dominated by individuals from our study, although traders and CAs were more active than farmers. Just 3% of successful sales were conducted by farmers from our sample, while 40% were by traders from our sample and 23% by CAs. 45% of successful purchases were conducted by traders in our sample and 25% by CAs.

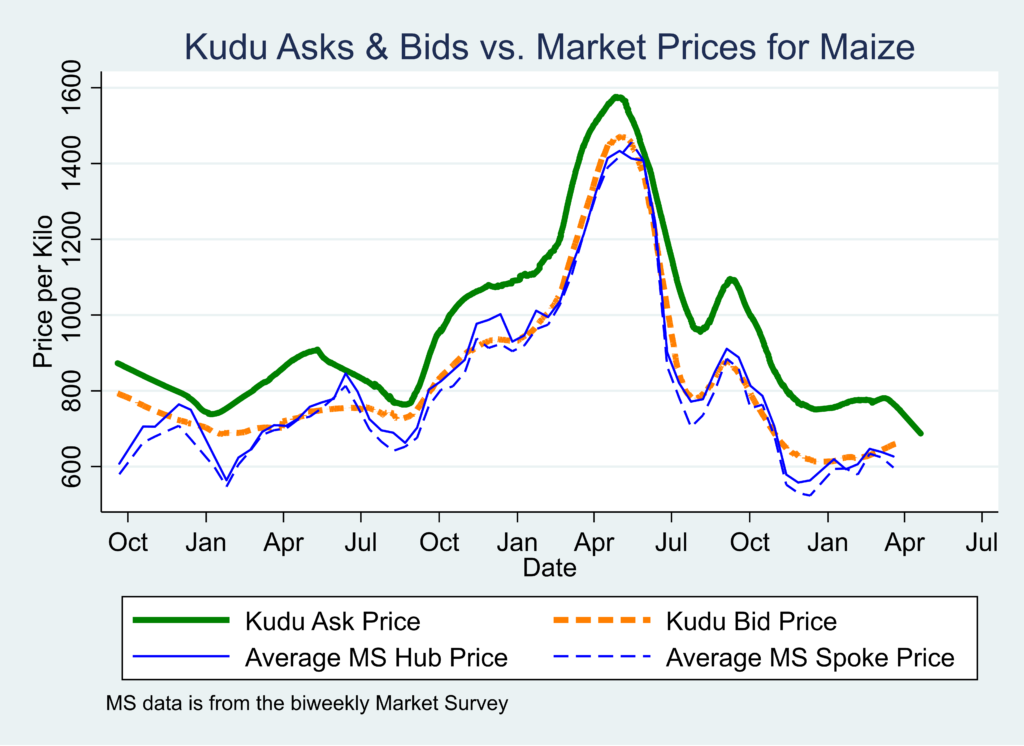

Kudu was built on the premise that it would serve as a marketplace in which sellers in surplus areas would post low asks and be matched with buyers in deficit areas posting high asks. However, surprisingly, we found through the study that the average ask price on the system was higher than the average bid price. Though the Kudu bidding system was designed to induce truth-telling (meaning that farmers and traders would list their reservation prices), it appears that there was a kind of ‘bargaining’ behavior where farmers commonly posted requests for prices that were substantially higher than those they could receive in local markets. The following graphic represents the evolution of buying and selling prices in the market survey of local markets versus on the Kudu platform:

Results

The results of the study suggest that this information/IT intervention was successful in triggering several forms of market convergence, but the resulting changes were not large enough to result in transformative improvements for farmers.

Market-level impacts

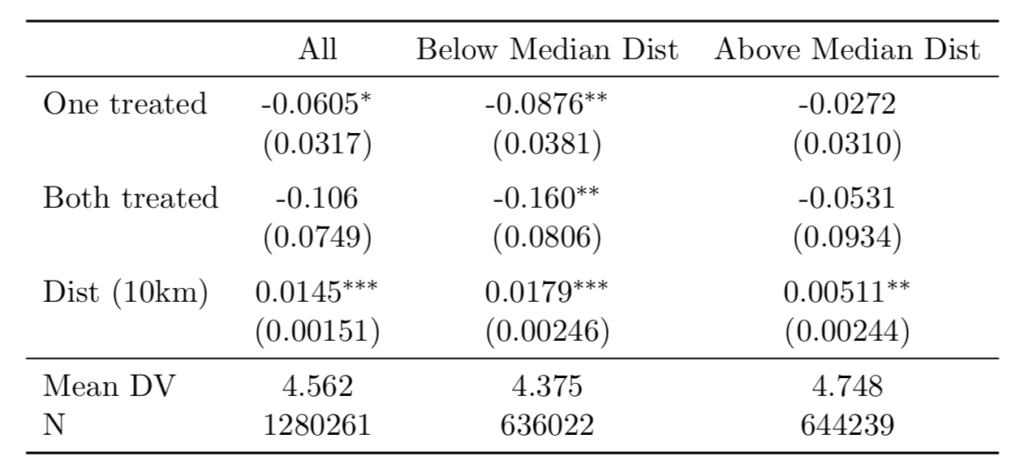

So, what were the effects of this platform? Starting at the market level, we see no evidence that our intervention shifted average market-level prices by a meaningful amount. However, we do find evidence that the platform drove convergence in prices. Treated markets experienced a decrease price dispersion with other non-treated markets by about 6% in maize (the primary crop traded on Kudu); when both markets are treated, we see reductions in dispersion of about 11%.

Examining heterogeneity in this treatment effect, we see the convergence is strongest among nearby markets, conforming to the pattern of business on Kudu, which was primarily relatively local (86% of the completed trades on Kudu were between a buyer and seller in the same district). This suggests that information may be most actionable in driving trade when other, more standard physical barriers to trade are low.

This intuition is confirmed by the market for tomatoes, the core perishable crop we studied. Here, contrary to storable grains like maize and beans, the markets are chaotic and highly autarkic. Despite the fact that our platform revealed and publicized substantial opportunities to arbitrage in tomato markets, only a tiny fraction of the trade in Kudu was for this crop (.07% of the asks and none of the competed transactions), and we uncover no evidence that the intervention influenced these markets at all. So, contrary to the conventional wisdom that information is most critical for perishable crops, our results suggest that when issues such as refrigeration create large transport costs in trading perishables it may be difficult to kick-start trade with information only.

To gain statistical power on the effects of SMS price information alone (separate from the Kudu platform), we “rolled in” over time a random subset of control trading centers to the SMS Blast treatment (many, though not all, were rolled in after the endline survey had been completed). This roll-in experiment combined with the high-frequency market survey data gives us a powerful way of looking for changes that occur as markets are brought into the SMS system alone. Here, we find a null effect on both price levels and price convergence, confirming the growing consensus that information-only price interventions are not very effective.

Trader-level impacts

By studying the behavior of traders in detail we can gain insight into the extent to which new information platforms alter their trading behavior. The fraction of traders receiving SMS price information from any source rose from 44% in the control to 86% in the treatment; the fraction who knew of a mobile-based platform that could be used to find buyers from 31 to 73%; the fraction ever posting a bid or ask on Kudu from 12 to 53%; and the fraction actually completing a trade on our platform from 4% to 28%.

More interestingly for the competitive dynamics of the market, traders also recognize a substantial improvement in the extent to which farmers are informed about prices in treated villages. The fraction of traders saying the farmers they negotiate with receive price information goes from 8% in the control to 26% in the treatment. Treatment traders say farmers are better informed, and the fraction reporting that price information had changed negotiations increased for transactions when study traders were buyers (5 to 16%) as well as when they were sellers (9 to 22%).

Consistent with this shift in relative information, particularly in the midline survey (one year into treatment) we find evidence of small increases in buying prices and decreases in selling prices, resulting in a significant reduction in the net profits of traders. The system therefore put pressure on intermediary profits, consistent with a meaningful share of traders’ profits arising from search-related frictions.

However, the platform did not transform the actual business practices of treated traders; they were no more likely to trade in more locations, to have traded with new trading partners, or to expand trading volumes of any study crops. Consequently, the platform primarily affected traders through a shift in prices that was negative for them.

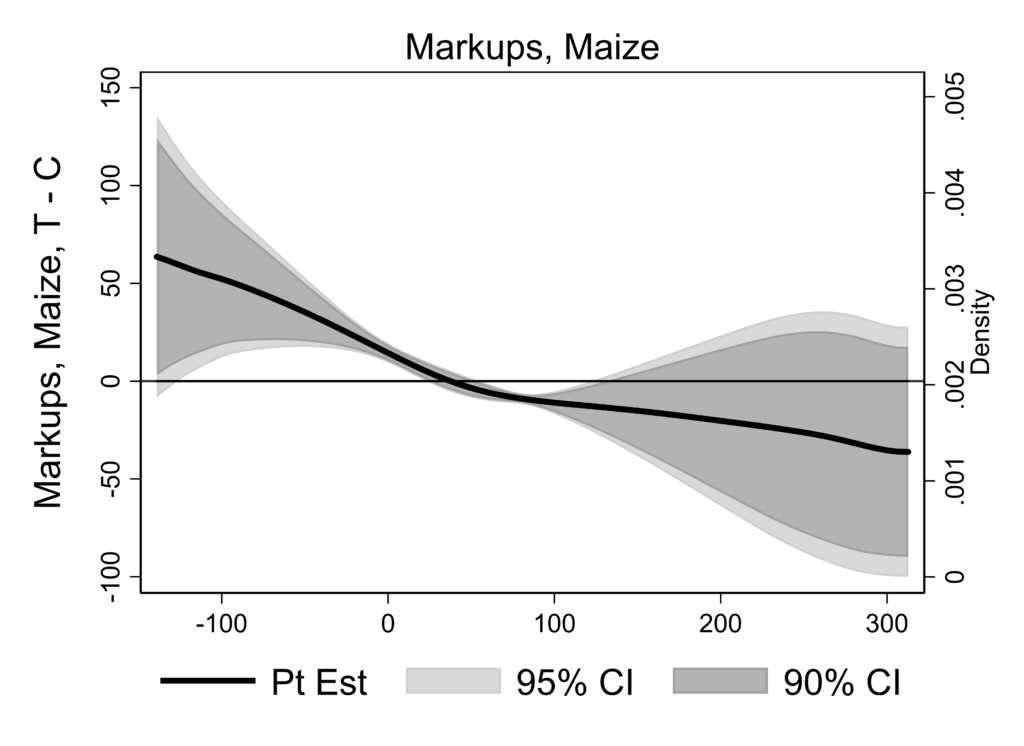

A second and distinct form of convergence triggered by the platform is in maize traders’ markup, the difference between the selling and buying price for a given trader. Those traders who had the lowest markups at baseline saw improvements in this margin arise from the treatment, while those enjoying the highest markups at baseline saw a deterioration. In other words, the treatment led trader markups to become more homogeneous.

Impacts on farmers

Finally, we explore how the intervention impacted farmer welfare. Farming households were randomly sampled, with nine farmers who live nearby to the study trading center and four who live further away (but in the same parish) randomly selected in each TC. Again, we see dramatic changes in reported access to information: the fraction of the treated households reporting receiving SMS price information was 45 percentage points higher than the control, the fraction who report using SMS information to negotiate when selling was 12 pp higher, and the fraction ever using Kudu was 11 pp higher. However, only 4% of the treatment farmers ever actually executed a successful trade on Kudu.

These improvements in price information translate into modest improvements in farmgate prices. Maize price treatment effects hover around 3% across the years of the study, significant only in the third year, and the most optimistic take on bean prices suggests an improvement of 6% in one year. These increases in price translate into increased revenues from beans during the first year of the program, but because beans make up a relatively small share of overall business the impact on total revenue is not significant. Correspondingly, there are no significant improvements in food security, overall consumption, and other core welfare metrics.

When we follow our PAP to look at heterogeneity by the propensity to use Kudu (ever posted a bid or ask, predicted from baseline variables) we find that the type of household most like to use Kudu (who are more likely to be male-headed households and to live farther from Kampala) respond to the treatment by deepening their exposure to both sides of the food market. They harvest, sell, and earn more from maize, but also increase expenditures on food. Prices, along with core welfare measures such as total consumption and food insecurity, are not disproportionately improved for this group.

A system connecting sellers of food to outside markets should be most effective when the price would otherwise have been low. We can study this by spatially interpolating a counterfactual price for all markets using only the control, and then analyzing heterogeneity in the market prices received by study farmers according to prevailing market conditions. Indeed, we see that the platform results in farmers receiving significantly higher prices specifically in seasons and markets that would otherwise have yielded low prices. Interestingly, these effects are most pronounced when the TC-level market price is below the average in the district (in the bottom tercile of the distribution of these market-level deviations from district average prices, treatment farmers receive 12% higher maize farmgate prices than the control group. The effect is not seen when the district average price is low overall. This is again suggestive of local but not long-distance arbitrage effects. Even in these cases, however, the price improvements are small enough that they do not translate into significant differentials in terms of net revenues or food security. Nonetheless, this impact is indicative of meaningful convergence and suggests that improved arbitrage provides an insurance-like dimension whose welfare benefits for risk-averse farmers could be larger than the pecuniary price change.

Takeaways

Mobile-based marketplaces for agriculture are often touted as a game-changer, capable of producing large improvements in farmer welfare. We do not find this to be the case, at least in our setting. The platform we tested did not shift market prices on average, and even for farmers directly treated by the platform, only increased prices incrementally.

Where the impact of the platform is clearer is in triggering four distinct forms of convergence: dispersion in prices across markets falls modestly, trader profits are significantly squeezed, markups across traders are homogenized, and farmgate prices rise when they would otherwise have been low.

We believe the correct interpretation of our results is not that information isn’t important or can’t result in major welfare efficiencies in isolated markets; however, it may be that the ubiquitous use of mobile phones in these markets has already achieved most of this benefit. Prior to the mobile revolution, price discovery presumably did include substantial costs, risks, and delays. Today, these costs are likely much lower, and therefore, the marginal benefit of improved search platforms may be weaker.

The gains we did observe resulting from this platform were in driving new trade almost exclusively in cases where the physical costs to trade were already low (storable commodities and nearby markets). In this case, interventions like ours may be effective in making markets more efficient on the margin, but they are unlikely to drive the kinds of transformative effects that have been documented in the face of massive investment in physical infrastructure that shift pecuniary trade costs.

The configuration we tested, using a private-sector intermediary to drive Kudu adoption on the ground while gathering commissions on brokered sales, did not turn out to be commercially viable. Despite enormous price fluctuations during the course of the study, these were mostly time-series in nature and opportunities revealed by Kudu for strongly welfare-enhancing spot trade were surprisingly rare. Contracting risk in these markets remains substantial, and arranging trade between previously unconnected parties is a challenge. However, fully scaled examples of similar technologies exist (such as AliBaba’s TaoBao) and it may be that the RCT-driven implementation for this study handicapped the technology relative to a full-scale commercial rollout. While the effects we find are modest, they are spread over a huge population and relative to their low costs and scaling potential, digital platforms may still be cost effective in many contexts. Efforts to create nationwide digital marketplaces for smallholders are currently underway in Kenya, Ghana, and a number of other developing countries.

The authors thank BASIS/USAID, ATAI, IGC, DIL/USAID, and an anonymous donor for generous financial support.